I read an interesting essay a few days ago, Moral Progress is Annoying by philosophers Daniel Kelly and Evan Westra. The premise is basically that when people advocate for a new norm we’ll often find it eye-rollingly annoying regardless of whether it’s related to something mostly arbitrary (that band isn’t cool anymore) or something that’s actually good (you should use a seatbelt in cars), so a sense of annoyance isn’t a reliable way to judge whether it’s good or bad but should prompt you to reflect and decide on the merits. I think the core of the argument makes some sense1, although I think they use some language and political hot-button examples in a way that may be polarizing2. In the TTRPG world we have norms about what to do while playing a game, norms in our communities and particular groups, and games about norms, so my thoughts went in a few different directions.

Mismatch Detector

The essay’s argument that you shouldn’t treat an emotional reaction that might be based on unfamiliarity as the deciding factor about whether something is good or bad but rather as a starting-point for consideration reminds me of my advocacy of following the rules of a new TTRPG to see how they work even if they’re contrary to your habits, instincts, or expectations. If you always go with your gut without paying attention then you end up ignoring potential new and interesting experiences (if it goes well) or data that there may be issues with the rules you’re using (if it goes poorly). The norm from traditional RPGs that the GM should selectively enforce rules or on-the-fly redesign them creates a weird bifurcated model where what’s happening based on your informal system can get attributed to a product (“This is a great game, we played a whole session without ever using the rules once!”) or what’s happening with the product can get attributed to your informal system (“We had a big argument about how to interpret this rule, how can I keep people from turning into Rules Lawyers so we can enjoy the game?”).

Norms and Familiarity

I thought the essay’s discussion of “norm psychology” was interesting and evocative in its own right. Here’s a section about being familiar with norms:

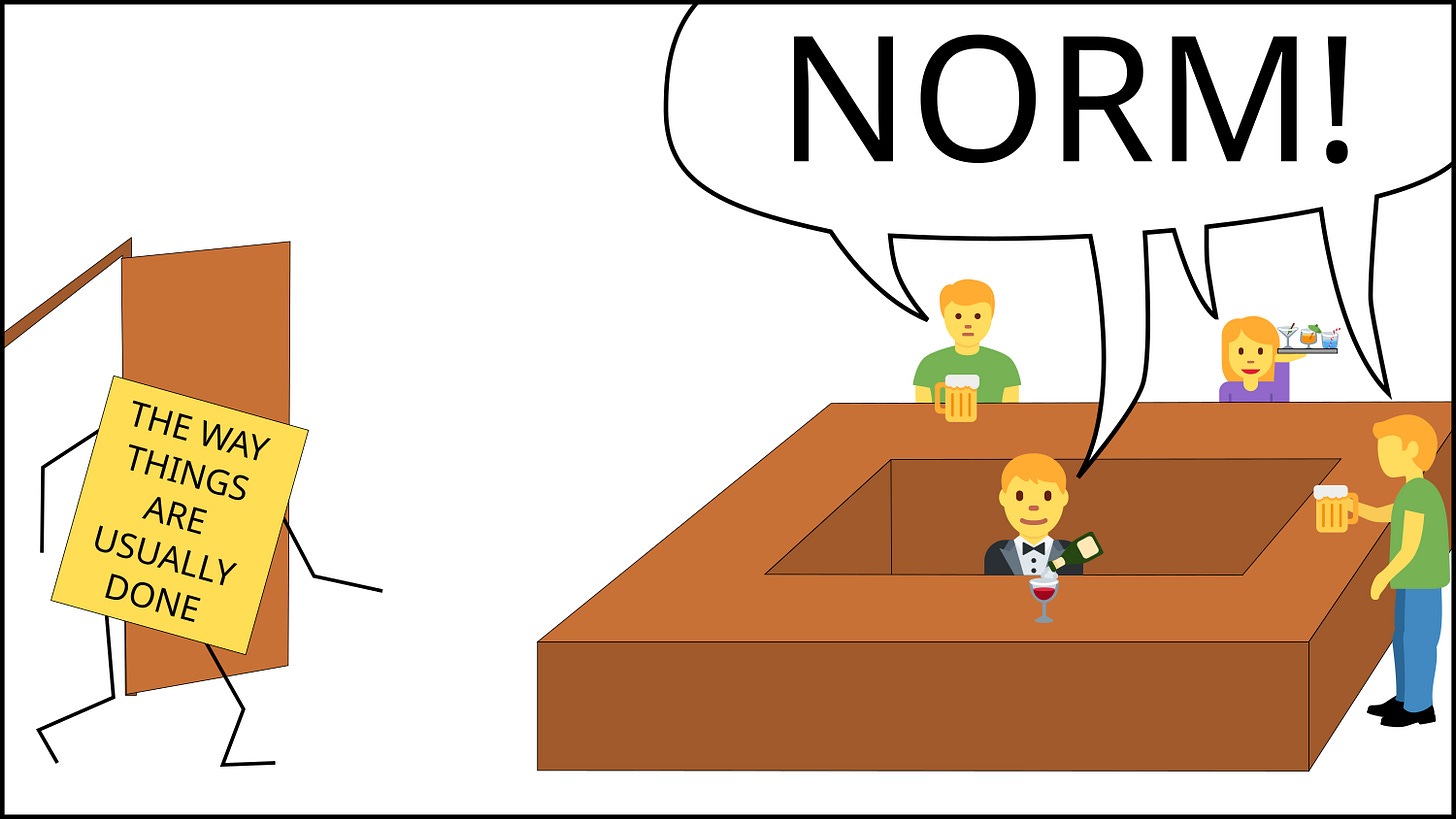

Our norm psychology consists of a cluster of emotional and cognitive mechanisms that helps us handle all these rules, allowing our actions to be steered by them, often effortlessly and without rising to the level of awareness. When our norm psychology is working properly, we glide through the norms of our social environment like fish through water. How much do you tip in the US? Why, 20 per cent, of course. Of course you don’t wear shorts to a funeral. You can curse around your friends but not your grandmother. In familiar environments, navigating norms like these is second nature.

That mention of below-awareness mastery reminded me of the way people talk about “flow state” which many people associate with being deeply engrossed in a game. Maybe there’s something related to that and the seeming desire for so many in the TTRPG space to have games that lean heavily on “play culture”, “unwritten rules”, etc. This is probably especially appealing for people who are adept at picking up local norms – there does seem to be something slightly magical about the way you can just “pick things up” by being immersed. By contrast, when people think about explicitly written rules they probably associate them with times when they are in an un-masterful early learning mode. Personally I don’t think there needs to be a conflict between explicit rules and masterfully internalizing a game – people can get really engrossed in playing a sport and those usually don’t have fuzzy rules – but thinking about it in these terms maybe helps me empathize a bit more with people who crave this way of engaging with RPG play.

Consider another example: Alice is visiting an unfamiliar country. She finds her fish-out-of-water experiences mostly enjoyable, relishing all the new, mind-expanding adventures she hoped to have on her travels. She knew she was going to be a stranger in a strange land and is thrilled to learn all the various ways they do things differently in the new culture.

But she also notices that common activities take a lot more out of her than back home. Ordering at a restaurant, taking the subway, walking down a street are all opportunities to be slightly out of step with others’ expectations. Even when she pulls them off without a hitch, social interactions take more effort and attention. When there is a hitch, it can be jarring and fraught, and by the end of many days she’s worn out by her clumsiness.

Alice feels discomfort because her norm psychology is misaligned with her social environment. The norms from her own culture, which she has internalised and is inclined to follow, don’t match the local norms. She is normatively and socially a little out of step with the culture she is exploring.

Personally, that sense of exhaustion is how I feel at the prospect of playing a game where I have to mind-read the “how to play” from everyone else’s expectations, and where the rules and structures of play are constantly subject to renegotiation or arbitrary change by the socially influential.3 I think that the “you’ll have to learn a lot of norms” thing can also work like a moat that’s built around hobby spaces. Maybe other people are more open to it than I am, but the prospect of needing to wade in to an already-established community in order to play is a big barrier for me and I doubt I’m the only one. Whether it’s the “convention scene”, local play groups, game stores, or online communities, I think that any established group of humans tends to start accumulating norms – that’s totally fine for the people involved (it would be weird if you have a friend group that never develops any inside jokes!), but if the only way to explore the hobby is to venture into these already-culturally-established places then it can be a barrier to entry. That’s part of the reason I wish there were better ways to casually form new groups for online play – if every participant is on an equally-unfamiliar social footing it might be easier to engage with.

Norm Entrepreneurs and Polarization

Affective friction can also strike closer to home. Even within a culture, times change, currents shift, and old norms give way to new ones. As this happens, some individuals can find that their norm psychologies have fallen out of sync with their own culture. This can gradually create the same kind of misalignment that happens all at once to travellers like Alice when they arrive in a foreign country. The experience of affective friction is similar as well: a loss of fluency combined with negative emotional signals arising from the gap between social expectations and realities. Even when the difference between an old norm and a new one replacing it seems trivial, the disruptions caused by the shift can create feelings of anxiety, awkwardness – and anger.

When people try to advocate for their preferred new norms in a way that feels overly aggressive or coercive it can cause polarization and lock groups into a mutually-antagonistic culture-war dynamic. I think this is why people can feel threatened when it feels like there are efforts to displace or undermine their style of play – for example, an earlier generation of over-enthusiastic Forge evangelists looked to traditionalists like they were trying to seize a cultural high ground and enforce their play preferences on the hobby. On the flip side, the name-calling and vitriol coming from some prominent anti-Forge-polemicists and Story-Games-haters felt like aggressive gate-keeping meant to wipe out that style of play.

This is part of the reason I’m skeptical of tactics like trying to enforce particular definitions of RPG Theory terms as a way to improve online TTRPG discussion culture – we’ve already seen previous cycles of that tactic and it contributed to the current environment. It could be that the problem with the previous definition wars was that those definitions were bad but it would work this time if you had good definitions. Maybe! But I doubt that’s the smart way to bet. There are some dubious terms and concepts floating around out there that I think are problems, but I think trying to attack them with high-leverage tactics rather than low-pressure persuasive arguments will likely make things worse. And to the extent that some of the subcultures are incompatible with each other, I think pluralism and figuring out better ways to allow people to non-antagonistically experiment and explore different approaches to TTRPG play without anyone needing to “own” the overall concept is probably a more stable strategy.

Some People Don’t Get Along with Dogs

In my opinion Dogs in the Vineyard is the high-water-mark of Forge era TTRPG design. In keeping with the “Narrativist” or “Story Now” zeitgeist, it was trying as much as possible to make character actions speak to morally-relevant themes in a moment-to-moment way. One way it tried to do that was with the setting: in our contemporary world a lot of people chafe under norms that they feel are overly restrictive. If those norms are arbitrary (or even malice-driven) then there’s not much of a dilemma, smashing the norm is good for everybody. But if the norms are important then there can be good reasons on both sides, so it’s something you can have a morally-relevant scene to explore. Dogs’ approach is to sidestep contemporary or historical culture and politics and put the action in a setting where there’s every reason for the characters to believe that the very strict norms are scaffolding that’s keeping people alive (possibly for supernatural reasons). Now there is tension – people being able to follow their hearts is good, but keeping disaster at bay is also good, so there’s no pre-defined way to figure out how to resolve the tensions, your characters have to be engaged in the messy particulars in a way that lets you explore in a humanistic way.

But some people, especially some on the political left, have trouble engaging with the setting. For example, they might be so committed to feminist principles that they can’t consider gender norms as anything but pretexts for inflicting subordinate status and violence on women, and therefore have no interest in enacting that. Or some might might see all authority as illegitimate, a mere license for bullying, rather than as something that comes with responsibility to use the authority appropriately. Some see depiction as implying endorsement, so they don’t want to engage with settings that have norms they don’t support. And some have norms about what the appropriate themes for particular settings are, for example believing that anything that evokes the American West must be stories about group conflict, racism, or seizing of land and resources.

On the one hand you could argue that any element of a setting ought to be fair game: some settings have magic or superpowers or faster-than-light travel and people can play with those fantastical elements without it being a big deal, so why not take the norm-relevant aspects of this setting on their own terms just like you would with those other elements? But on the other hand maybe it’s easier to engage with obviously fantastical elements than things which are arguably still in political contention in our world, plus there’s no accounting for taste: you can not-vibe with a setting for good reasons, bad reasons, or no obvious reasons at all, there’s no obligation to like or dislike any particular artwork. But I think the most interesting things that Dogs has to say relate to violence and authority, not things like gender roles, so I think it’s unfortunate if the gender-norms, etc., of the setting get in the way of people engaging with those other aspects.

But, because the setting does some of the “heavy lifting” in what makes Dogs work as a game, I think you need to be thoughtful about how to play in alternate settings4. The setting ideas I contributed to the Threeforged 2019 game Embers of Spite were inspired by contemplating how to do a Dogs-like game in a setting that tries to align with, rather than rub against, some of the things I’ve seen be barriers for people with Dogs: it’s a fantasy world with no connection to real-world history, most bad things are caused by an inchoate force of malice based in the past, but the old bad order has already been eliminated by a combination of it’s own failures and a popular revolution, so the action in the setting involves building communities going forward. And the aspect where the group brainstorm-elaborates on the norms of the particular communities is likely to come up with things that may seem interesting or unusual, but probably not seem intrinsically morally-suspect for the people playing that particular game (since people would be unlikely to pitch ideas like that). I don’t know if it works since it’s an unplaytested jam game, but I think the idea of taking the norm-psychology of certain subcultures into account as a virtual constraint for game design was fruitful for me in coming up with interesting setting elements.

Part of this is the nature of politics, if a chunk of the political spectrum stakes a claim on the term “progress” then discussing anything “progressing” may read like an endorsement of those political ideas. But also it seems that the authors are sympathetic to many new Progressive norms and see them as beneficial even though they are still disputed. It may have been useful to include early-20th-century Progressive’s enthusiasm for eugenics as a helpful illustration that not every idea coming from self-identified progressives is actually good (although contemporary Progressives may not see that as being associated with their movement, so I’m not completely sure that would work). Another possibility is anti-nuclear and anti-infrastructure-building norms established by mid-20th-century environmentalists that seem to be in tension with current efforts to lower carbon emissions to work against climate change (although I think that only works if you agree that nuclear is better on multiple dimensions). I think it’s tricky to try to discuss the topic in a politically relevant way without risking alienating some segment of a potential audience.

I struggle with social anxiety and feel like a socially awkward outsider in a lot of situations. That middle paragraph about being out of step resonated with me as a good description of how I feel about a lot of social situations.

Some people think that Yoda’s Jedi philosophy aphorism “Fear leads to anger, anger leads to hate, hate leads to suffering” can map to the Sin Ladder and easily translate Dogs to a Jedi in the Vineyard setting, but I think this is a mistake: This teaching seems to be about what can happen within a person not what reverberates in a community, and the supernatural influence of The Dark Side seems keyed to those strong in The Force: Jedi teachings are mostly for Force users not for the general public. There’s no obvious map for how to set up an analog for a Dogs town such that personally elevating oneself above the norms that are supposed to be binding starts an escalating spiral that puts the community at risk. You could map it to a “whoever’s using supernatural powers must be the bad guy” type of town, but that’s not a good Dogs town.