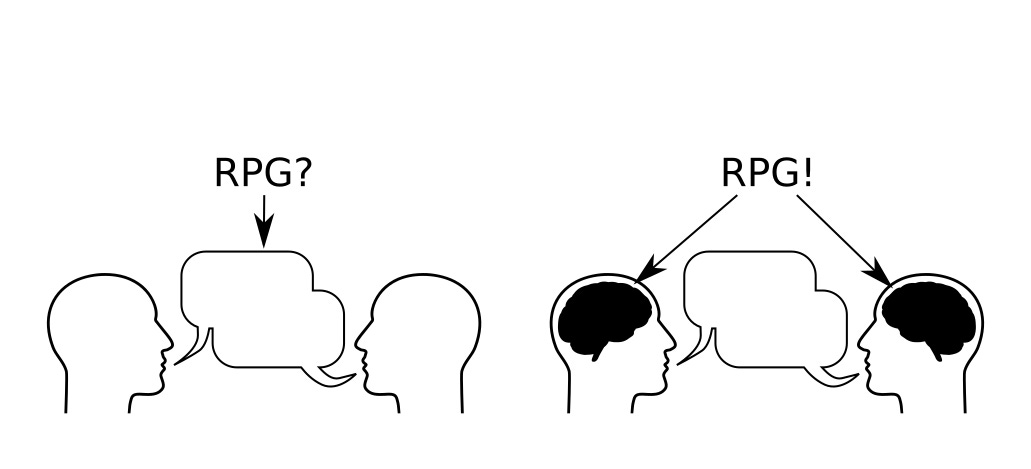

A Roleplaying Game is Not a Conversation

An RPG is a game of the imagination

In the indie TTRPG world the idea that a roleplaying game is a conversation was popularized by Apocalypse World and the Powered by the Apocalypse framework. I think this is a thing that’s either saying so little that it’s trivially true but not very useful, or else making a stronger claim that’s actually wrong.

Everything is a conversation

A lot of things can be described as conversations, and the line between literal and metaphor is pretty fuzzy. An artwork can be described as a conversation between the artist and the medium, or between the artist and the audience. A chess game can be described as a conversation between the two players. Sure, all perfectly valid uses of the word. If conversation just means thing that involves interaction then an RPG is indeed that, but that’s so obvious that it isn’t clear what value is achieved by taking a detour through a different word to say so. However, my understanding is that in the TTRPG context Vincent Baker meant it more specifically, in the “words and talking” sense of conversation.

Not just talking

I agree that words and talking are an aspect of RPG play, but if you describe playing an RPG as “a kind of talking” you might not be wrong, exactly, but it puts the attention in the wrong place. Someone could describe the process of me writing this article as “a kind of typing”, but if someone heard that I was doing “a kind of typing” they would be thinking about things like touch-typing vs. hunt-and-peck, not the process of working through ideas and considering how to express them that is the main work of writing an article. RPGs involve talking, but the main action involves what’s happening in our imaginations.

Shared Imaginary Space

Orthodox Forge Theory talked about the Shared Imagined Space, the things that are collectively imagined as a result of what people expressed at the game table. Framing things this way was an understandable attempt at simplification – a single resolved space is a lot easier to work with than the messy multi-agent system of multiple people’s imaginations. But as some people said at the time and others are saying today, the reality is that what’s happening inside people’s heads is an important aspect of what’s happening during RPG play and you can’t always simplify it away. “The fiction” is not a recollection of what people said it’s the state of things right now in the virtual imaginary world of the game. That shared world is an abstraction, implemented by the imaginations of the players being kept in sync with each other during play. But because humans are good at that sort of thing, that’s sufficient for that imaginary world to be part of the “game state” that makes an RPG what it is.

I’m Just Sayin’

Even though I think it’s a mistake to say that an RPG is a conversation, communicating is an aspect of RPG play and it makes sense to think about it. The real insight that contributed to Apocalypse World’s design was the recognition that humans have a lot of habits and instincts related to conversation that can be incorporated into a game’s design. AW doesn’t include a specific mechanically-mediated back-and-forth turn-taking structure because it expects the way people talk to each other will organically incorporate that into the proceedings, and it largely works.

Games do need some element of “no-take-backs” that transform hypothetical considerations into actual new game-state that can be the basis for the next step in exploration, and in RPGs speaking things aloud can be part of that. Getting things from your thoughts out into spoken (or written) words externalizes them and makes them more concrete. In RPGs that’s usually not the whole of it (most games have room for table-talk and let people toss ideas around or revise things they’ve said) but the need to explicitly articulate your contributions is usually an aspect of the way RPGs function as games.1

Discourses & Definitions

A lot of people strongly oppose talking about definitions. Sometimes they reference horror stories about silly philosophical rabbit holes with “necessary and sufficient condition” style definitions. Other times they’ll imply that all efforts at thinking about categories or definitions are malicious gatekeeping, referencing events like claims that Paul Czege’s My Life with Master wasn’t really a roleplaying game because it had an endgame. There’s an understandable human instinct to react to the negative tone of “That’s not a game!” or “That’s not an RPG!”, but we don’t need to throw the baby out with the bathwater.2 There are lots of wonderful activities that aren’t roleplaying games, there are some roleplaying games that are bad experiences: whether something is or isn’t a roleplaying game isn’t a reliable source of information about whether it’s a good or bad thing. Saying “that isn’t a roleplaying game” doesn’t have to be an insult, and “that is a roleplaying game” doesn’t have to be a compliment. It sometimes takes effort, but it’s possible to engage in nonjudgmental categorization or labeling without getting into emotion-laden namecalling, and it’s possible to say that someone’s categorization argument is wrong without ditching the concept of categorization altogether. The problem with the “MLwM isn’t an RPG” argument wasn’t that categorization is ipso facto bad, the problem was with the wrong idea that RPGs need to be open-ended perpetual games.

So, what is an RPG?

I think that RPGs are games where a significant element of play involves interacting with a Shared Imaginary Space through the lens of particular characters. This is a definition without crisp borders, but that’s fine. The shared imaginary space seems to be a characteristic element of RPG play that distinguishes it from other types of games (boardgames, card games, strategy games, sports, etc.). I go a step further and assert that engaging with that world through particular characters is what makes it a roleplaying game rather than just any game of the imagination.

RPGs and Storytelling Games

It seems to me that the “roleplaying” of interacting with the SIS through particular characters has the salutary effect of reinforcing the “reality” of the shared world – when you “step into” it to understand your character’s situation or exert their influence you’re reifying that world by acting as if it’s a solid foundation. It also tends to calibrate people’s contributions to a meaningful not-too-big not-too-small scale because we tend to have good intuitions about the scope of what “a character” can do. In contrast I’d say a “storytelling game” is one where you’re engaging in more whole-cloth-authorship of “the fiction”. That orients players differently, highlighting how changeable it is.

Back on The Forge some people developed the idea that the basis of roleplaying games was “narrative authority”. In broad strokes, the first step was to imagine a situation in which a player, Bob, could say “My character bonks the orc on the head with a club” and the orc would then take damage. They then mapped this series of events to a pattern:

1. Bob said something

2. The orc took damage.

And then they concluded it would be completely equivalent for Bob to have said “A chunk of rock falls from the ceiling onto the orc’s head” and then the orc takes damage. It maps to the same pattern! That theory, however, was wrong: these things feel different in play because they orient the player differently with respect to the SIS. These experiments with Narrative Control mechanics3 were interesting, and it was a reasonable hypothesis to consider, but I think what they show us is that mechanics like these feel more like a storytelling game than an RPG.

A case study: Last Year’s Magic

“There is nothing so practical as a good theory.”

– a quote attributed to psychologist Kurt Lewin

Thinking about the definition of RPGs that I’ve presented here was useful to me when I was doing design work on the game Last Year’s Magic4 during the original Threeforged design jam. This was a three-round design jam where designers would start a game design in round one, their work would be anonymously passed around to a different designer for round two who would (ideally) build on it, and then that would anonymously go to a third designer for round three to complete the game. In the second round I got a game design which involved players describing fantasy-world tavern patrons interacting with each other, in a way that always circled back to a steady state of “busy tavern”. Because this was storytelling about characters rather than roleplaying as characters and everything always returned to the same position I snarkily characterized it to myself as “a non-roleplaying non-game”.

After I worked the snarky grumbling through my system I was able to reframe this as a challenge to myself: how do I take this and make it into a roleplaying game while keeping as much of the spirit of the original as I can? The game I got already had some card-related mechanics, so I decided to fix the “not a game” aspect by tying the “return to a steady state in the fiction” element to being in a different mechanical position: your decisions in each round use cards from a hand that doesn’t replenish, so your choices have subtle repercussions across rounds. For the roleplaying aspect I wanted to try to get the player to engage with the world from the POV of their character, so I made the game about wizards attempting to glean nuance from cagey statements about how magic works in their fantasy world. Someone from our world might be tempted to scoff at “spiritual power” and “the imposition of will upon reality” being indistinguishable, but if you put yourself in a headspace that considers these distinctions important then you’re closer to the headpsace of the wizards in this game and will be better able to surf the nuance that lets you communicate and interpret the communication of others in the trick-taking aspect of the game.5

So what I ended up with wasn’t a conventional or traditional roleplaying game, but I think it’s a Roleplaying Trick-taking Card Game. I think the cards matter, and I think the roleplaying matters. I think if you just roleplay without taking the card game part into account you’ll do poorly at the game. And I think if you try to just play the card game while treating the roleplaying as meaningless fluff you’ll also do poorly at the game. I claim that engaging with both is important.

When I’ve tried to play story-rich boardgames like Arkham Horror solo I find that it’s a qualitatively different experience than playing with a group. When there are other players, the “need” to read aloud for them prevents me from slipping into a mode where I just skim for the “real” mechanical parts. The “story” aspects of those games is usually epiphenomenal in a way that a good RPG isn’t, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the need to express your contributions in an RPG contributes to them feeling and being richer than when they’re just thoughts in your head.

Cue some Star Trek aliens that might think the distinction between babies and bathwater is needlessly pedantic.

Which is not the same thing as “Narrativism”. In fact most of the games regarded as being Narrativist-friendly didn’t have explicit Narrative Control mechanics. But because the words are similar it’s a common assumption to think they’re related even though they’re not.

I’d like to be able to point to an easily downloadable draft of this, but current practices in the indie TTRPG world don’t sit comfortably with the shared creative ownership. If it was a solo project I would put it up on itch as a pay-what-you-want, but as a shared project I don’t want to deal with the overhead of figuring out how to equitably share random tips that might come in with a coauthor, but eliminating the awkwardness by preventing payment also seems weird.

Some people who tried out the game and podcasted about it as part of their Threeforged coverage framed the various suit categories as all essentially the same, which to me sounded just like people who think that the Apples to Apples or Cards Against Humanity mechanic is pure randomness (no, those games are about playing the judge for each round), which paradoxically made me more confident that I had baked some good design into this game that they didn’t perceive properly. (Of course there’s a chance that my belief is self-serving self-deception, being able to observe playtests would provide a more objective answer).

This was a fascinating to read. I love the idea and phrase "Shared Imaginary Space," and I will add it to my vocabulary and way of thinking about Roleplaying Games. I am working on a game right now, and I am really trying to understand how I want to approach the project. This was very helpful. Thank you.

Thank you for this!

My TTRPG friends and I have been faced again and again with people who have come into the "

TTRPG hobby" from Forge games, PBTA, Blades in the Dark, etc. The games that literally state "A Roleplaying Game is a Conversation", and then never again use the word game when describing them.

We always felt that this wasn't right, it wasn't wrong, but it was incomplete.

Storytelling games and traditional RPGs both get called RPGs. This is just clearly wrong, they're not the same. If we're going to insist that they're both RPGs then they're at least completely different genres, similar to how a first person shooter, and a point and click adventure game are very different genres in video games.

But the storygamers insist that their storygames is what TTRPGs always were supposed to be, that they are an evolution and that traditional RPGs are bad, outdated, and nobody should play them. I don't mind that storytelling games exist, I just want people to stop lying about them.